Discuss organ donation

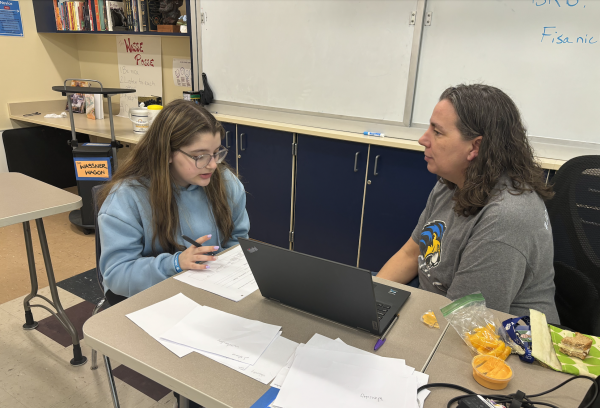

Nearly 115,000 people in the United States are currently waiting for a lifesaving liver, kidney, heart, lung or other organ transplants, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Jewish text teacher Grace McMillan’s husband was one of them, until he received a kidney transplant from his father who has a matching blood type and antigens.

McMillan recognizes that her husband is lucky. Not only did he find a compatible relative, but a kidney, just like a partial liver or intestine, is an organ that only a living donor can provide.

“For many people, the best match can be somebody within their family, but not always,” McMillan said. “So the broader the pool is of available organs, the better chance there is to find a match.”

The problem is that the pool is far too small. A person joins the national transplant waiting list every 10 minutes, yet there is a severe lack of donors to meet the growing demand—such a shortage, in fact, that an average of 20 people die each day waiting for a transplant. The wait is often longer for the 2,000 children and teenagers in need of a transplant; in many cases, they require donations from another child of a similar age or size.

Teenagers have the opportunity to register as an organ donor when they get their driver’s license. Before doing so, though, teens and their parents should educate themselves on the matter and discuss each other’s preferences

Common misunderstandings about medical care, potential suffering and costs related to organ donation may deter parents from letting their teenagers register, according to a C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health at the University of Michigan. Just one in four parents who participated in the poll said that their driving-age teen is registered to be an organ donor.

Let’s clarify some misconceptions. According to the University of Michigan, being an organ donor will not affect the medical care a person receives in any way. They would still get all treatment options in a life-threatening situation. Furthermore, a person does not need to be kept alive for a donation and will not experience any additional pain. There is also never a cost to the donor’s family for an organ donation.

Whether or not they choose to register, teenagers must discuss their donor preferences with their parents or legal guardians. If they don’t, then the burden of that decision would be placed on a teenager’s parents in the event of a tragic accident. And not all hospitals may have personnel trained to have this type of discussion with a grieving parent.

“That’s a horrible decision for parents to have to make,” McMillan said.

Jewish tradition considers saving a human life to be among the highest acts of virtue, equivalent to saving an entire world. But precisely because life is sacred, the practice of taking organs from the dead is fraught with delicate ethical questions and complicated laws surrounding the definition of death. Several traditional requirements—to bury the dead quickly and avoid any defilement—would seem to prohibit taking organs from the dead. However, the lifesaving potential of organ donation is generally regarded as overriding those strictures, according to My Jewish Learning.

No teenager should feel obliged to register as an organ donor, or at least not the moment they turn 16. It’s a conversation to have with a proper factual basis between teenagers, their parents and possibly a rabbinic authority. But if there’s even a small chance you could save someone’s life—and one donor can save up to eight—then registering is worth it.

This story was featured in the Volume 36, Issue 4 edition of The Lion’s Tale, published on January 25, 2019.