A smarter way to learn Hebrew

Five years ago, CESJDS invited the organization Hebrew at the Center to audit its Hebrew language program. After visiting teachers’ classrooms, reviewing the curriculum and interviewing faculty, Hebrew at the Center’s experts shared a report with recommendations for the school.

JDS considered the results and, in 2015, partnered with Hebrew at the Center to implement the Proficiency Approach, which prioritizes student simulation, to language instruction. The goal was to “elevate Hebrew language learning at the school,” Head of School Rabbi Mitchel Malkus said in an email, with a teaching approach that emphasizes student participation and discussion.

Now in its third year, the Proficiency Approach has reaped more than just competent Hebrew speakers, Malkus and other Hebrew teachers said. It has created a community where Hebrew is alive in every student and ingrained in our school’s cultural fabric.

Writing and speaking skills are widely regarded as the most difficult for language students to master. And while writing gives students time to organize their thoughts, conversations require that a broad understanding of grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation be at hand on a moment’s notice. For this knowledge to be readily accessible during a conversation, students must practice speaking. A lot.

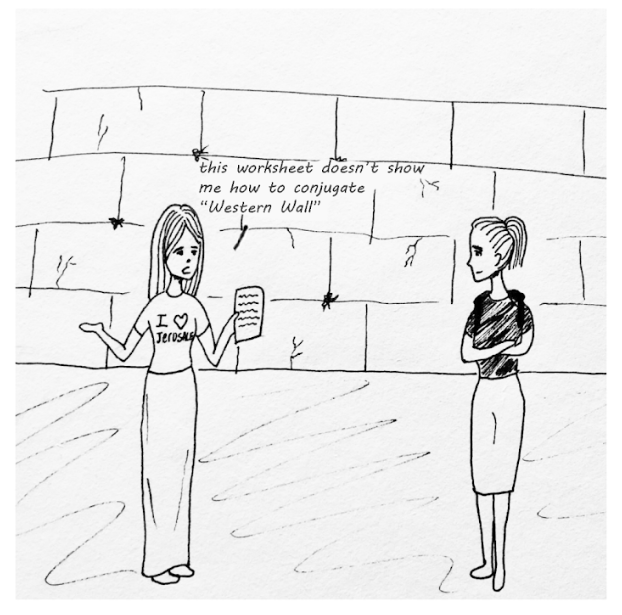

Even though JDS students usually spend just three to four hours a week in the class, the best method is a complete Hebrew immersion. During this time, it is tempting to revert to English among friends. It is only if teachers “arrange the class so that every part has discussion,” as Hebrew department chair Hannah Rothschild said, that students will practice.

The warmup, or chimum as it is called in Hebrew, is a particularly valuable exercise that puts students in the “speaking mode,” distinguishing the period as one dedicated solely to Hebrew speech. At the beginning of every class, the teacher might pose a question about Israeli current events, students’ personal lives or perhaps an interesting ethical dilemma.

The goal, according to Rothschild, is to get students comfortable speaking “about any kind of topic.” It does more than that, though. A proper warm up lets students discuss matters that are engaging or personally meaningful to them, which makes the study of the language itself more appealing. It is also an opportunity to learn and immediately implement new vocabulary. Speaking can effectively cement novel words into students’ minds, but only if they are revisited in the near future.

Often when teachers set aside time for speaking, discussions begin at individual table clusters and end with the entire class. Back-and-forth conversations between students simulate how they will likely use Hebrew outside of school, but speaking in front of a class is just as worthwhile. When a teacher listens to a student speak, they can identify and address gaps in the student’s vocabulary and grammar that writing assessments may not reveal.

Hebrew class allows students to use the language the way it was intended: as a tool for communication. A person learns their first language by listening to others and trying to imitate what they hear, so new languages should be learned using the same approach.

When JDS students graduate, the Hebrew language stays alive in them through conversation. By emphasizing speech, then, the Hebrew department gives students a gift that will stick with them long after they leave class.

This story was featured in the Volume 36, Issue 2 edition of The Lion’s Tale, published on Oct. 26, 2018.