Journey to Jordan: Arabic student embarks on cultural exploration in the Middle East

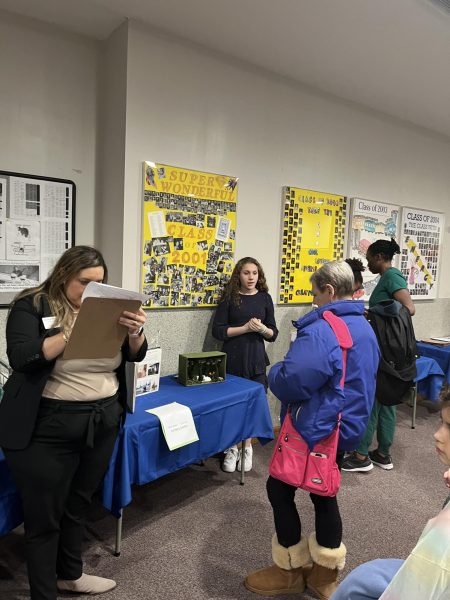

Photo courtesy of Ari Gershengorn

Gershengorn, his classmates, teachers, staff and host parents pose for a final picture, after presenting his final project about shawarma. According to Gershengorn, Jordanian shawarma costs only $1, in comparison to the typical $11 cost in Israel.

September 1, 2017

When a taxi driver casually asked Ari Gershengorn his religion, the CESJDS junior looked out the window, and as the Arabic street signs whizzed past him in Amman, Jordan, he said: “Christian.”

“I probably didn’t need to lie, but I didn’t need the complication in my life,” Gershengorn said.

Gershengorn took a leap into the unknown political and religious landscape of Jordan this summer, studying Arabic at the National Security Language Initiative for Youth (NSLI-Y) program in Amman.

The NSLI-Y program is an intensive State Department immersion experience that teaches strategic languages including Arabic, Chinese (Mandarin), Hindi, Korean, Persian (Tajiki), Russian and Turkish to high school students and recent high school graduates.

After stocking up on long pants and other modest clothing, Gershengorn was ready to go.

“I was nervous,” Gershengorn said. “I had never done anything like it.”

Prior to the trip, Gershengorn had previous experience with the language. He has taken two years of Arabic at JDS, tutored Syrian refugees and studied Arabic with Middlebury interactive languages at Green Mountain College in Vermont last summer. He plans to use Arabic in a future career and hopes to work in the State Department or overseas one day.

“It is really useful for me to be able to speak English, Hebrew and Arabic,” Gershengorn said. “There is a high demand for people with that skill set and and a low supply.”

In Jordan, Gershengorn was the youngest participant in the program, with the fewest years of high school Arabic under his belt.

“We were really excited for him,” Ari’s father Ian Gershengorn

said. “This seemed like a great opportunity for him to study Arabic where it’s spoken by natives.”

Ari lived in Jordan for six weeks, learning the country’s language, culture and history. He spent four hours, five days a week in formal classroom instruction. He devoted the balance of his time to other programming, including speaking Arabic with 18-year-old Saif Jankhot, his Jordanian language partner.

“It gives you a good way to practice your Arabic in a low stake setting,” Ari said.

Outside the classroom, Ari was impressed by the food in Jordan. After class, he and his friends went out to “sample all the shawarma restaurants we could.”

Ari and his friend Sally Egan decided to write their final class project about Jordanian shawarma. Visiting as many restaurants as they could, they tasted the chicken shawarma, eating multiple plates a day. They established a 1-10 scale for shawarma, based on flavor, atmosphere of the restaurant and the opinions of local patrons.

“They had this entire algorithm on how to grade, to find ultimately what was the best shawarma in Amman,” said Laila Mohamud, Ari’s classmate from Seattle.

On one long bus ride through the desert, the students were provided shawarma for lunch.

“Me and my low standards; [it] was great,” Mohamud said. “I was like, ‘free food.’”

But mid-bite, Mohamud turned around to find Ari and Egan rating the chunks of meat, comparing their lunch to the shawarma throughout Amman.

While shawarma in Israel can cost $11, in Jordan it costs only $1, he said.

“It might be because they have low health standards, but whatever, it tasted delicious,” Ari said.

He did not get sick, but there were other hazards to watch out for in Jordan, including calling attention to himself.

“Don’t stand out,” Gershengorn recalled his instructor telling the students during the safety briefing at orientation. Although Gershengorn didn’t feel afraid to tell people he was American he found it was easier to avoid the topic as people would immediately ask about Trump.

The safety instructor told the 16 young Americans to avoid the poor side of Amman, the refugee camps. “They prepared us for the worse case scenario,” Gershengorn said.

The closest brush he had with violence was on July 23, when a Jordanian man attacked an —Israeli embassy security guard with a screwdriver. Ari lived a mile and a half away.

“It was a little spooky, but there was never a point where I felt like I was in any sort of danger,” Ari said.

Ian said that at the start of Ari’s trip, he was “anxious” about sending Ari off to a foreign country.

“We put our faith in the State Department and it turned out to be well placed,” Ian said.

Ari traveled safely to Petra, the Red Sea and other famous landmarks in Jordan. He visited museums in Amman and made friends with Jordanians.

“There’s obviously value in learning the Arabic and being around native speakers, ” Ian said. “But I think the bigger value is being on your own in a foreign country, and learning to navigate around a country, and really experience a different culture.”

One Friday night, Ari attended a free summer music festival. Dancing with Jordanian men to the beat of Arabic music, the group drifted into the family section and started chatting with local children. Security guards stepped in and ejected Ari, along with his new Jordanian dancing partners.

“It was kind of a fun thing to bond with the people, that we were about to get kicked out of a dance festival by Jordanian security, which is not really a sentence I would have imagined myself saying a year ago,” Ari said.

And now he can say that very sentence — in English, or he prefers, in Arabic.