U.S. veteran interviews

November 12, 2016

For history teacher Michael Connell’s War and Civilization class, seniors were assigned to interview a U.S. veteran. These are six of their stories:

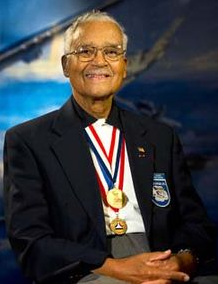

Colonel Charles McGee

Colonel Charles McGee served in the U.S. Air Force for 30 years, over which time he set the Air Force record for most combat mission flown over a three-war period with 409. McGee was one of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first group ever of African-American airmen in the United States Armed Forces who broke barriers set by prejudice through their service. After serving in World War Two, the Korean War and the Vietnam War, McGee retired from the Air Force.

Colonel Charles McGee served in the U.S. Air Force for 30 years, over which time he set the Air Force record for most combat mission flown over a three-war period with 409. McGee was one of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first group ever of African-American airmen in the United States Armed Forces who broke barriers set by prejudice through their service. After serving in World War Two, the Korean War and the Vietnam War, McGee retired from the Air Force.

(photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force)

Senior Jonathan Foldi: Why did you first chose to join the Air Force?

Charles McGee: Well, I really tell folks I was avoiding the draft. I had a draft card, but because I was in college the board wasn’t pulling my number. When I heard about the aviation opportunity, I went and passed the exams for the pilot training and had to wait a while and got called up a few months later. I would say after my first flight in primary I knew I’d made the right decision. Had I been drafted, I’d learned to handle a rifle in ROTC, I would have been, I called it “ground pounding” back then, on the ground in the mud. Being able to go up in the air and loop, roll and spin and come back and put your feet on the ground was a thrill.

JF: Was there anything that you had done when you were younger that influenced you?

CM: No, I was not one of those that said as a youngster “I want to be a pilot some day” looking up at an airplane flying over. It was just happenstance that it was a good choice for me because I fell in love with aviation and ended up with a 30-year military career. Of course segregation brought some of that because in the late ‘50s, airlines weren’t hiring black pilots or women for that matter, but I had wonderful opportunities so it was a great experience.

JF: How large of an impact did segregation have on you during your service?

CM: Segregation actually had become a part of army policy based on a 1925 War College study that, they called it facts that we were able to dispel, but the ‘fact’ that we were not physically qualified to do service work but mentally and morally not able to do anything technical such as flying an aircraft. That was sent to Washington to become part of army mobilization policy and Washington accepted it. When we first declared war against Hitler in Europe, the opportunity to get into military aviation was denied, but the pressure from around the country for participation and due to the fact that the need was still building, the army said they’d experiment because they’d studied the issue and knew it’d fail, but it didn’t. Fortunately though through the war, the army didn’t change the policy, but when the Air Force separated from the ground element they made the determination that integration was an important step.

JF: Throughout your career how did you notice the Air Force becoming more integrated not only in policies but also in the actions of individuals?

CM: Yes, that came about I’d say during the war years 1941-45, the army didn’t change the policy. The Air Force separated from the ground forces in 1947 determined to integrate. Their action was backed by President Harry Truman who actually order Executive Order 9981 mandating that all services needed to integrate so the Air Force finally closed the segregated base the 1st of July, 1949. Those of us still on active duty were scattered around the world.

JF: At any point throughout your service did you reconsider your career choice?

CM: Well, I was enjoying flying, but they came along and said “You can’t just fly, you have to do something else.” So I went to aircraft maintenance officers school so I was qualified for management in the materiel area as well as being a pilot. As I say, I couldn’t have written a better script for opportunities and was fortunate enough and I say very lucky to actively fly 27 of my 30 years so I was having a good time.

JF: How were your experiences with integration different overseas than they were at home?

CM: There was still segregation really, even though the Army and Navy had followed [Executive Order 9981] in the Korean timeframe, until the Civil Rights movement there was still segregation. Mostly related in some cases to schooling and children and certainly to travel, motels, hotels and restaurants were often denied because of segregation. In the early ‘60s after the Civil Rights movement had opened, we also began to get assignments here at home cause after the first integration I would say most of our good assignments were overseas and that began to change. It took our Air Force leading the country in providing equal access and equal opportunity for everybody. Certainly based on, as the Air Force said, training and experience and not happenstance of birth.

JF: Are there lessons you learned during your service that you carry with you today?

CM: Yes because you learn awful lot about leadership and what that means. You learn a lot about working with people. It’s almost like saying in the military you become a band of brothers. Of course you’ve taken an oath and the training was good so it’s a matter of living by what you took the oath for and it was a great experience

JF: Were you aware during your service of your Air Force record for the most combat missions flown over a three-war period?

CM: Well probably to say it correctly it’s the Air Force record with 100 or more combat missions in each of the three wars: I had 136 in Europe, 100 in Korea and 173 in Vietnam, but I had no idea [of the record] even well after retirement. It was at one our our conventions, when the Chief of Staff of the Air Force General [Ronald] Fogleman spoke at one of our conventions and said that record existed.

JF: What do you view the legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen to be?

CM: Really the legacy is that, as I mentioned a little bit earlier, getting an education is certainly a step that is important because we all had to get the right education to take advantage of the opportunity when it became available. Certainly believing that you can and finding what you like to do and hope you stick with it is another part of the legacy. I tell some of the young folks about perseverance and by that I mean don’t let circumstances be an excuse for not achieving. We could have gone off saying “they don’t like us, they don’t want us” and not done anything, but we wouldn’t have served our country, nor would we have in most cases like mine ended up with a wonderful career. Who knows if we hadn’t performed and dispelled those biases and generalization what that would mean to our country and what the Air Force would become.

Captain Leonard Green

Leonard Green, Captain of the Medical Corp during the Vietnam War, grew up in Queens, NY. After attending Yeshiva University and Albert Einstein Medical School, Leonard served in the United States Army as a Neurologist in Valley Forge Hospital in Valley Forge, PA. He then went on to be a neurologist in Youngstown, PA for over 25 years and is now retired, living in Washington DC.

Leonard Green, Captain of the Medical Corp during the Vietnam War, grew up in Queens, NY. After attending Yeshiva University and Albert Einstein Medical School, Leonard served in the United States Army as a Neurologist in Valley Forge Hospital in Valley Forge, PA. He then went on to be a neurologist in Youngstown, PA for over 25 years and is now retired, living in Washington DC.

(photo courtesy of Noah Green)

Senior Noah Green: What was your branch of service?

Leonard Green: US Army Medical Corps, starting in 1966.

NG: What type of training did you receive to perform your duties?

LG: I was drafted. I was required to go. You had to report to duty and such and such a date. I was already a doctor and I had already finished my residency, but I had to get trained to be an officer in the army. I had been in practice for year after my residency.You had to learn rules of being an officer, when to salute, when not to salute, how to dress, and then they gave you some combat training. Well for doctors they treated us separately as a unit, we didn’t train with the regular army, we trained as the medical corps. But we learned how to handle a pistol, .45, the standard pistol was a .45. We had target practice and they also taught us how to use a compass, they took a group of us out and they dropped us out some place in the desert and we had to find our way back to the central area. And a lot of the doctors who were surgeons they were taught how to suture wounds, and they wounded some animals and they had to sow them up. I didn’t do that because I wasn’t a surgeon. In basic training you learn how to march, marching is not simple. There is an art to it. “Left face, Right face, About face.” You have to follow commands.

NG: Where did you receive this training?

LG: I first reported to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. I was at Fort Sam Houston 2 weeks or 4 weeks, I don’t remember. It must have been 4 weeks.

NG: To what unit or units were you assigned?

LG: My final posting was the Valley Forge General Army Hospital in Valley Forge, PA. I was made the senior officer for Neurology.

NG: Where did you serve during the war with this unit or units?

LG: I served at Valley Forge General Army Hospital in Valley Forge, PA.

NG: What were your duties and responsibilities during the war?

LG: My duties consisted of, well, Neurology didn’t have its own ward of patients, I was part of the internal medicine department, but if they had a neurology question they would request a consultation and we would go and see the patient, who were soldiers and their dependents, their wives, children, grandparents. If they were injured overseas they would go to the big orthopedic department over there, cause a lot of them were amputees or had injured limbs. There was 200 patients there or so. The hospital also had a large psychiatric service. My duties specifically were treating psychiatric patients, inpatient and medical, orthopedic patients, and I ran a clinic for outpatients, usually for dependents or other army people who weren’t attached to Fort Valley Forge, or other army units around Philadelphia. Other than saluting my superior officers it was basically normal doctor work.

NG: What were some interesting and memorable experiences you have from the war?

LG: I didn’t do any actual combat, but I heard a lot of stories from the soldiers who were hospitalized. There was one young black soldier in the orthopedic ward, he had a leg wound, told me that he was stationed near a river and the enemy was shooting from across the river, and one of his friends got killed. He got very mad and one night he swam down the river, crossed the other side, and killed with his knife, some six or seven enemy soldiers while they were asleep and swam back. He must have been 20-21 years old, he was a real tough guy. We had some real interesting cases that we had never seen before, we had a case of periodic paralysis where suddenly he would get weak all over and then get paralyzed. It was a hereditary condition, somebody in his family had it and we had to treat it, it’s a very rare condition and I never saw a case like that before or after him. We saw paralyzed patients and we evaluated them for the rehab department. We also had an interesting teenager dependent who had a particular sleep condition called Kleine-Levin Syndrome. Periodically every few months he would be overcome with extreme desire to sleep and he would sleep for days. Days, he would only get up to grab something to sleep and then run back to his bed. He couldn’t stay awake. We did some tests on him and at that time they thought it was a psychiatric condition, but we found out that it was really a neurological condition because he had [a medical condition’ that we found on him. I never had a patient like him again. I wrote a paper on that, published in the archives of neurology journal.

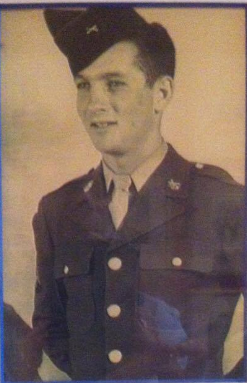

Private Don Greenbaum

Private Don Greenbaum served in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1945 as an Artillery Forward Observer for the 283rd Field Artillery Battalion. After landing on the beaches at Normandy, Greenbaum was tasked with locating enemy positions and relaying back the coordinates. On April 25, 1945 his unit was tasked with seizing supplies at Dachau, but instead discovered and liberated the Dachau concentration camp.

Private Don Greenbaum served in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1945 as an Artillery Forward Observer for the 283rd Field Artillery Battalion. After landing on the beaches at Normandy, Greenbaum was tasked with locating enemy positions and relaying back the coordinates. On April 25, 1945 his unit was tasked with seizing supplies at Dachau, but instead discovered and liberated the Dachau concentration camp.

(photo courtesy of Eli Winkler)

Senior Eli Winkler: What was the most disgusting thing you encountered or faced during your time in the Armed Forces?

Don Greenbaum: Liberation of Dachau Concentration Camp as we did not know about the camp and while we were on our way to capture Munich we were told to destroy the supply depot in Dachau and on our way to destroy the supply depot we came across this awful odor and the sky was black and we did not know why and then we came across boxcars full of dead bodies which is where the smell emanated from.

EW: What was your first thought when you entered Dachau?

DG: We did not know what it was and I thought it was a supply depot and then I found out that 90% of the people there were Jews in line to be executed

EW: How did you communicate with the survivors?

DG: We did not, but there was one man in the unit who spoke Yiddish and was able to tell the survivors that we were the American army and that we came to help them and the survivors were ecstatic.

EW: Did you meet any resistance when you went to liberate Dachau?

DG: No we did not as all the guards tried to mingle with the prisoners by dawning prison garb, however, the rest of my unit and I was able to recognize the guards and we would either kill them or the guards fled. We could tell the difference between prisoners and guards based on who looked better cared for.

EW: Had you heard anything about what was going on in Dachau before you went in to liberate the camp?

DG: I had never even heard the expression death camp or concentration camp before and only came across the camp when my unit was told to go to destroy a supply depot in Dachau as I said above

EW: I saw on the History Channel & Fox News that Ernie Gross (a survivor of Dachau) reached out to thank you. What was that like for you?

DG: What happened was my wife appeared in the Jewish Exponent (Philadelphia’s Jewish newspaper) and it was mentioned that I was a Purple Heart and involved in the liberation of Dachau and Ernie called the Jewish Exponent which called me and then I called Ernie and we had lunch together and we have been speaking together for seven years going around the country talking about the war.

Major General Michael Ennis

Major General Michael Ennis served in the Marine Corps across the world including Japan, East Germany and Washington D.C. He served in intelligence, being promoted to Director of Marine Corps Intelligence in 2000.

Major General Michael Ennis served in the Marine Corps across the world including Japan, East Germany and Washington D.C. He served in intelligence, being promoted to Director of Marine Corps Intelligence in 2000.

(photo courtesy of U.S. Marine Corps)

Senior RJ Firestone: What was your final rank?

Michael Ennis: Marine Corps Three Star General.

RF: What type of training did you receive to perform you duties?

ME: The way the Marine Corps does it is [that] I went to officer training school. It is, in the Marine Corps, the first 12 weeks of OCS (Officer Candidates School) is not training- you’re not training to do anything. The first 12 weeks is simply to screen individuals to see if they have the potential to be an officer in the Marine Corps. So it’s more of a screening course. The first 12 weeks are spent at Quantico, Virginia where the Marine Corps weeds out those who weren’t thought to have the potential. Interestingly enough, also in the Marine Corps, the instructors in OCS are all enlisted, who have served under officers in combat situations or other situations. And they’re the ones who are going to determine who in their estimation will be the best because they’re the ones who are actually going to have to follow the orders of a 2nd Lieutenant. So they want to make sure they have a vested interest and then make sure that the candidates have the right qualifications and the potential to become officers, people they would feel comfortable being led by.

So then, once you successfully pass that, then you get a commission in the Marine Corps and you go to six months of officer training. This is where all Marines, irrespective of what they want to be, I don’t care whether you want to be a baker, cook, or a pilot or in communications, or whatever, every single 2nd Lieutenant is trained to be an infantry officer for the first six months. And after that, then you go onto your specialty training. Whether its intelligence, or engineering, or whatever. So I chose infantry, so at that time I didn’t have any further training. So that was the initial training. And then there was a program that was actually started by the Army in 1947 was called the Foreign Area Officer (FAO) program. And after eight years as an infantry officer, I went to be trained as a FAO. This is where I got a Master’s degree in Russian studies. Then I went to Monterey, California for a year to study intensive Russian and then I went to Germany where they had an enclave of Russian emigrates, dissidents, defectors, a lot of them were Jewish actually, lawyers who had been evicted out of the Soviet Union. And we spent two years, there were only twenty of us and it was an enclave of native Russian speakers. Former KGB, lawyers, doctors, whatever. I did that for two years, and I did not lose my infantry occupational specialty. I kept my infantry, and then I did that training. That was the training that essentially prepared me for my future career.

RF: Where did you receive this training?

ME: OCS was at Quantico, Virginia. The basic school was at Quantico, Virginia. Language training was in Monterey, California and then advanced Russian training was at Garmisch, Germany. At the same time, I got a degree in Russian studies from the University of California. They flew in instructors from the U.S. to teach there in Garmisch, so that’s where I got my degree in Russian Studies.

RF: What war or wars did you serve in?

ME: Well I was in the Marine Corps, during the Vietnam War, although I never served in Vietnam. I was going to the National War College when Desert Storm/ Desert shield so I was not involved in that. I was the G2 of the Marine Corps. when 9/11 occurred. And basically my job was to insure that the Marines going into the attack in Iraq were trained, equipped, and had the right personnel to go there. I was in Iraq several times but I wasn’t actually involved with combat operations. And then when Afghanistan became more prevalent I went to Afghanistan on a number of occasions to work with Marine units there and DIA conducted clandestine covert operations. It was not combat, you can’t call it combat. The only time I was ever shot at was when I was on patrol and we came across some Spetsnaz (Russian special operations forces) who shot at me three times when I was trying to escape through a small village. That was the only time I was close to really getting blasted away or whatever. Although I did in Ramadi, Iraq, I was on foot there for two days, and it was pretty hairy. I was involved in all of them but never actually in a combat unit during the operations.

RF: What were some interesting and memorable experiences you have from these wars?

ME: I would say that my most interesting assignment, without doubt, the whole reason I went into the FAO program, the whole reason I wanted to do the job in East Germany was because in the 1970s and the 1980s, there was no war going on and I wanted to go to combat. I wanted to go prove myself as an infantry officer. And there was one of my classmates while I was going through Russian training was shot and killed in East Germany, and it was a pretty hairy assignment. We went where the Soviets didn’t want us to be and they had a habit of ramming our vehicles, catching us and detaining us, in some cases shooting at us, or in some cases, two of my colleagues were killed just before I arrived there in 1985. So I did 150 patrols in East Germany, some of them were routine, some of them got to be very tight: Rammed vehicles, escape on foot, being chased on foot, being shot at, trying to gather the information to be sure that the Soviets were not secretly under cloud cover trying to mass a conventional attack. We didn’t have the satellite coverage then that we do now so they were the most exciting. I’d say the second one was probably when I went with General Mattis into Ramadi, two weeks after, literally two weeks, Al Qaida had cut the heads off of 14 young boys and put their heads on the steps of the Mayor’s office in the center of Ramadi. We were trying to make a point that Ramadi was clear. We went with just a sidearm, and just walked through the village, talking to elders, and just trying to make a presence. We did the same thing in several other Iraqi villages too. We were trying to make the point that we were here and things were safe. Frankly I can think of a better point than going in and walking around on foot for six or eight hours. In Afghanistan it was interesting to see how things had changed. I first went to Afghanistan in 2004 and we had our long rifles over our shoulders and we went out to dinner downtown and we actually drove from some of the monuments and some of the graveyards, and some of the other things, we actually drove from there to the airbase up there. You can’t do that anymore. You can’t go downtown anymore there, we drove up in an unarmed vehicle dressed in haji gear, so that was kind of interesting.

Captain Rabbi Irving Elson

Captain Rabbi Irving Elson served in the United States Chaplain Corps for 35 years, half of which was with the U.S. Navy and half of which was with the U.S. Marine Corps. Elson has served in Japan, Iraq, California and currently the Pentagon. He is also a CESJDS parent, father of sophomore Abby Elson.

Captain Rabbi Irving Elson served in the United States Chaplain Corps for 35 years, half of which was with the U.S. Navy and half of which was with the U.S. Marine Corps. Elson has served in Japan, Iraq, California and currently the Pentagon. He is also a CESJDS parent, father of sophomore Abby Elson.

(photo courtesy of Abby Elson)

Senior Daniel Baumstein: Could you tell me more about your life, your time in the military, why the US Navy, why you decided to become a Chaplain?

Irving Elson: When I decided to become a Rabbi I had a very, very dear mentor to me my Rabbi growing up and he’s the one who kinda put the idea in my head. Saying you know when you become a Rabbi you should join the military just for a couple years get a little experiences, see the world a little bit and then after that you can get a local congregation. So that kinda planted the idea in my mind. Now my dad is a veteran. He fought in the Korean War as a Marine. He was very insistent that everyone no matter who they are or what they do should serve in the military as service to our country. So between those two I said okay. When I graduated college and Rabbinical school I joined this program, it’s like an ROTC program for students trying to become a Rabbi. I started in 1982 as a reservist and I just fell in love with what chaplains do and who they are and what they represent. I was a reservist for my five years in Rabbinical school and then when I got ordained I came on active duty, it was called augmented, moved up to active duty. Originally my wife Fran and I were only going to come in for three years and at the end of the three years we were like, well maybe another three years, then maybe another and 35 years later here we are. Why the My father was a Marine, but the Marines don’t have their own Chaplain Corps [so they] use Navy chaplains and Navy doctors. I like the mission of the Navy and I especially like the mission of the Marines. I think the Navy kind of mans the ship and the Marine Corps trains the man, the person. They are very much into creating the leader. You know they were the first ones to come up with honor, courage and commitment as a core value. Later on the the Navy picked that up. So that was the main reason for joining the Navy.

DB: What is the role of the chaplain?

IE: The main role of the chaplain is, let me back up, the Constitutional role of the chaplain, is to guarantee the right to freely exercise your religion in the military. What that means is just because you join the military as a sailor or Marine, just because you raise your right hand and swear to protect the Constitution doesn’t mean that you give up your right to practice Judaism and Christianity primarily. So that’s the main role, we are the facilitators through which people are able to exercise their right to religion in the military. So what that means is if there’s a Catholic sailor who wants to attend Mass I would try to facilitate that. A lot of times when I was a battalion chaplain I would arrange a helicopter to bring a priest into our unit to say Mass. By the same token guarantee a Jewish person can attend a Seder or observe Shabbat as best they can. At the same time we take on this other role of serving as the spiritual guide for the men and women in the military. We do a lot of counseling. You know serving in the military is a very high-stress, high-paced environment; young people come in and a lot of time we offer them that. The third thing we do is provide advisement to the commanding officers in terms of religion. More and more we are being placed in places around the world where religion is part of the conflict. We serve as advisors on what role religion plays in the area. So starting a major offensive on a Muslim holiday in a Muslim country would not be the best idea.

DB: Are Chaplains just in general multi-denominational?

IE: Well yes and no it’s kind of complicated. For religious things we only do our faith. I can’t and I don’t know how or what to do Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, Buddhist, etc. services. But what I do do is facilitate other services. What we say in the Chaplain Corps is that we provide for our own [faith,] facilitate for others. For example if I was the only chaplain in a unit and I needed someone to lead Protestant services I would make that happen by getting another chaplain to come in. We care for all, for spiritual counseling what we call pastoral counseling that is across the board for all. So if a sailor or marine comes to my office for counseling no matter what their religion may be or if they are of no religion at all, I am going to provide that pastoral counseling for them. I would say about 80% of the problems we deal with are spiritual but not religion specific. They are life problems.

DB: What would you say was your favorite experience or memory you have?

IE: They are all great. I love serving with Marines. I hated being in combat but that was the most gratifying. I liked being in the carrier navy, I was already pretty senior by then so my job was to inspect the chaplains on these carriers so I would get to fly all over the world and get aboard Navy aircraft carriers and inspect the chaplains. Every one has been great, I haven’t had a bad experience at a duty station. Even the Pentagon which a lot of people hate I thought was really interesting and got to do a lot of stuff with policy about gays in the military, transgenders in the military etc. That’s where you serve as an advisor. It’s pretty much all administrative. I did a little bit of manpower, one of my jobs was to figure out how many chaplains we are going to need in the Navy 10 years from now. I did policy for the Marine Corps, religious policy like, right now there’s a movement about whether or not you can wear beards in the Marine Corps, so every one has been different.

DB: What values do you think your time in the military has provided for you?

IE: One of the big values is service. The more I did the more I got to see yeah everyone needs to serve their country somehow whether it’s in the military or community service, that’s one of the big values. Also honor, something you don’t see a lot of in corporate America, but it’s a big thing in the military and discipline.

DB: You mentioned your time in combat, can you describe that a little more especially as a chaplain?

IE: Combat in general is you’re always tired, always hungry, always scared. It’s pretty horrific, the Marines are fighting and you’re kind of in between, you are trying to see how they are doing. They have a lot of questions, a lot of anger, they are upset and scared so you kind of try and hold them all together. Especially when your unit takes causalities, whether it’s wounded or killed in action, so you’re trying to help them process everything that’s going on while at the same time trying to keep them on mission. It is very, at least the war in Iraq, was very fast paced, like go, go, go, so when you had an hour or two pause that was really when your job starts. You walk around asking how you doing and that’s really when the floodgates open. You experience, well the Marines experience, a whole wide range of emotions: being really angry and wanting to kill everybody to war is terrible, you know civilians die and you see all sorts of horrible things. It’s something that I am really proud that I went through but it is something that I hope I never have to do again. Yeah combat messed me up pretty bad it changed me quite a bit. The whole experience changes you.

DB: Now after your retirement from the Navy after 35 years, what’s the next step?

IE: I still have a lot of fight left in me, in about another month I will be starting another job working for an organization called the Jewish Welfare Board. It’s a not for profit that represents the American Jewish Community to the Department of Defense. I am going to be the liaison between the American Jewish Community and the Department of Defense we also take care of Jewish chaplains as well works a lot on policy.

Officer Aaron Atterman

Officer Aaron Atterman served for a total of 27 months in Iraq over the course of two separate tours. Atterman served an Armor Officer and was assigned to the Eighth Infantry Regiment.

Officer Aaron Atterman served for a total of 27 months in Iraq over the course of two separate tours. Atterman served an Armor Officer and was assigned to the Eighth Infantry Regiment.

(photo courtesy of Ethan Kane)

Senior Ethan Kane: What type of training did you receive to perform your duties?

Aaron Atterman: Four years of military education as part of the West Point curriculum, as well as six months in the officer basic course. Every day we had on-the-job training and learning from the officers who outranked us in Iraq, it’s a constant learning experience

EK: Where did you serve during the war with this unit?

AA: First deployment: Fob Paliwoda in Balad, Iraq. Second deployment: Mosul, Iraq.

EK: What were your duties and responsibilities during the war?

AA: First deployment: A Tank Company Executive Officer and a Tank Platoon Leader. Second deployment: Battalion Assistant Operations Officer, then a liaison officer doing intel work involved in lethal targeting. Performed operations with the Iraqis, during the point where we were trying to transition the lead on combat operations to the Iraqi.

EK: What were some interesting and memorable experiences you have from the war?

AA: We had a couple of times that we would be celebrating something, like finding a big weapons cache, you know some mission went very well. And then literally while celebrating that mission because everybody got home safe, you get a call ten minutes later that someone out there got killed. It kept you on edge a little bit because there was always that possibility that in a heartbeat someone can get killed. There was never a time when we were having a bad day and someone got killed. It was always a time when we were having a decent day and then something went terribly, terribly wrong. So something always just kept that in the back of your mind.

I remember the first time I went out into Iraq. I left the base, put on all of my equipment, got in the vehicles, and we went out with what we had with us. There were these giant mile-long, like a hundred truck convoys that were called Third Country Nationals. So I think this guy was Filipino, his semi-truck had been hit by an IED and I guess he tried to get out or something, so we were driving along in one of our units securing this smoldering truck and the driver was smoldering on the side of the truck. They were just sitting there waiting for the fire to be put out so they could cover the body. It hits home when you literally see people dead on the side of the road.

I remember that the first time someone got injured in our unit really messed us up. Our commander, the battalion commander, was sitting there and he’s like “I don’t understand, you guys cannot be this distraught over someone getting hurt. He’s alive, he’s going home to his family. Yes, he’s injured and he’s not going home the same, but he is going home.” That was the worst we’d seen, and it made sense until someone died that, you’re right it could have been a whole lot worse.