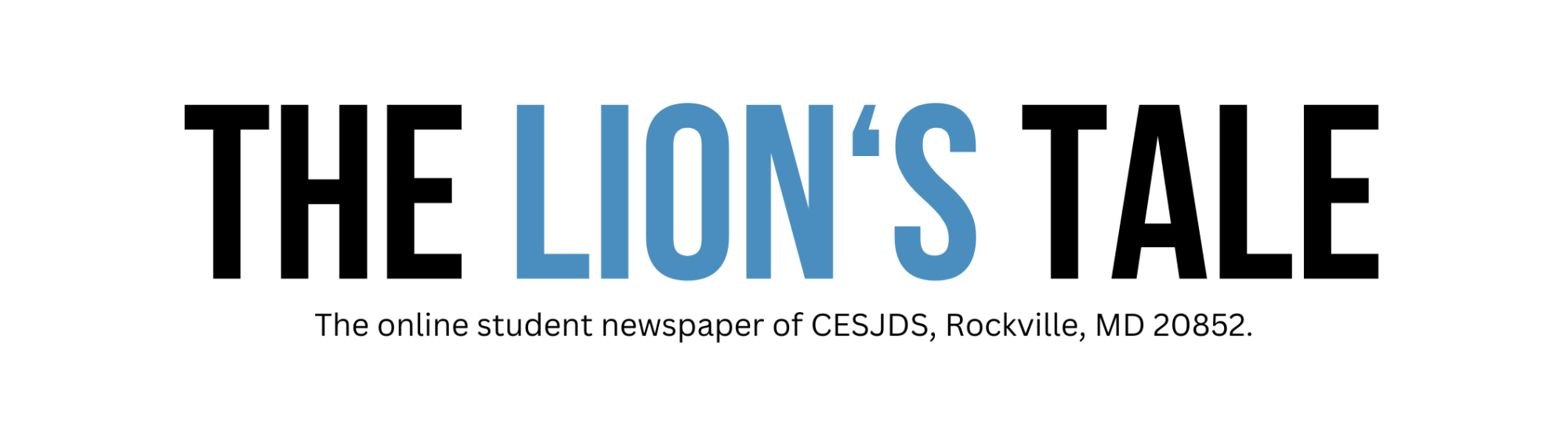

After hearing Jonathan Shimriz’s, a survivor of Oct. 7, first-hand account of how he survived the day, and the tragic story of his brother’s death during an assembly, the student body rushes to class, where we are expected to start learning immediately. This abrupt transition harms the student body, as by not allowing us the time to process, we become emotionally numb and less responsive to what we have just learned.

While I often see this scenario as I transition from assemblies back to classes, I also see it after Jewish history class, or mini-lessons about what is going on in Israel, to the rest of the learning during my school day. As a result, I see peers of mine struggle to focus or feel empathy toward whatever situation we just learned about.

“[The presentations] lose so much meaning when we’re just thrown right into class afterwards,” junior Maya Greenblum said. “Not only that, it’s emotionally uncomfortable to just go to class; it feels almost like we’re disrespecting the time that we just had.”

By not processing the traumatic information that has just been shared with us during assemblies and harder class content, my peers and I are forced to suppress our emotions. Hearing these difficult experiences becomes our new normal, and we are no longer surprised when we hear something horrifying.

“I think [this emotional numbness is] part of a broader feature of society that we’re experiencing right now in general, which is a combination of the fact that we have access to so much news,” Maharat Ruth Friedman said. “And so what psychologists talk about is: it’s not normal, and therefore they would argue not healthy, that we are constantly exposed to so much horrible news.”

According to Unity Point, a common response to this news overload is emotional numbness. This numbness can be helpful because it calms us temporarily, but over time, it can have prolonged consequences such as disconnection and detachment. Easy ways to counter emotional numbness include mindfulness, spending time with loved ones and exercise.

According to Psychology Today, spending time processing harder information can have long-term benefits, such as a more insightful outlook on difficult situations and better health. It takes different people different amounts of time to process, but we all must do it.

I appreciate that it is extremely difficult for CESJDS to schedule extra time into the day for students to process after difficult assemblies or classes. As such, I appreciate that on Yom HaShoah and Yom Hazikaron, we took some time between assemblies and classes, and I urge the school to continue to do this on other occasions.

However, I acknowledge that sometimes there isn’t enough time in the schedule for a long processing period.

“I think the biggest thing [you can do] is trying to reset yourself when you can,” high school guidance counselor Marnie Lang said. “Even if that’s like, okay, that just happened. It was a lot. And then taking a minute to do … anything that will help you transition from one thing to another that you know works for you, I think is the best way to then pivot back to class.”

To counteract the possibility of emotional numbness and lack of response, I encourage teachers to give students a few minutes to debrief as a class and students to take an extra minute to think through whatever event we just had and to try to process it to the extent that they can fully empathize with what was just learned.