Life as a rabbi’s child

Grappling with the question of whether to follow in their parents’ footsteps

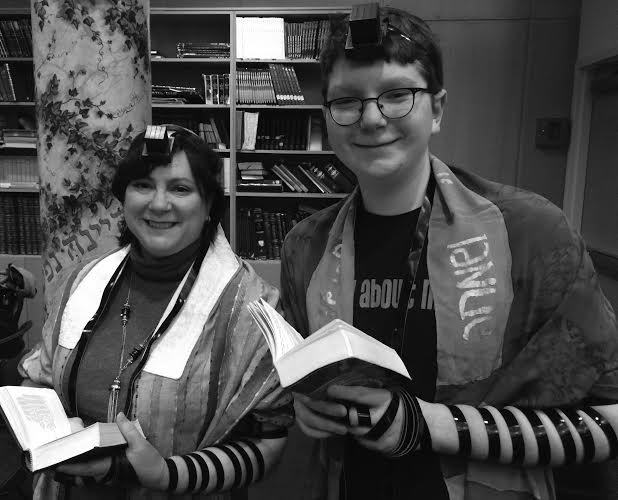

Senior Manny Bass and his mother, Jewish Text teacher Janet Ozur Bass, pray daily in the same Zman Kodesh.

January 31, 2016

For some kids, ‘bring your child to work day’ happens at the doctor’s office or the bank. For others, ‘bring your child to work day’ happens every Saturday.

Junior Nadav Kalendar, whose father is a pulpit Rabbi at Congregation Olam Tikvah in Virginia, said that his home life revolves around Judaism because of his father’s position.

“At home my family talks a lot about Judaism and I grew up learning all about it,” Kalendar said. “[I] have gone to Israel every year of my life, which definitely helps me learn more and more.”

But Kalendar still cannot see himself choosing the same career path as his father.

“I definitely won’t follow my dad’s footsteps, even though I love that he’s a rabbi,” Kalendar said.

Just like Kalendar, senior Mikhael Hammer-Bleich does not want to be a rabbi. When Hammer-Bleich goes to graduate school instead of rabbinical school, he will be breaking out of three generations instead of one.

“My dad is a rabbi, my granddad is a rabbi and my great granddad was a rabbi,” Hammer-Bleichleich said. “In many ways I will and in many ways I won’t follow in their footsteps. One way that I will copy my parents is that I will be open with my kids and allow them to make their own choices when it comes to religion.”

Though Hammer-Bleich appreciated that his parents allowed him to view Judaism more open-endedly, he sometimes felt that Judaism presented a “my way or the highway” attitude, which ultimately caused his “less religious” lifestyle.

For Hammer-Bleich, that lifestyle meant realizing that “there is more to Judaism than just extreme religion and obsessive Halachic following.” He even screamed that he was the rabbi’s son during a service because his sister dared him to.

Senior Mikhael Hammer-Bleich (bottom right) has mixed feelings about his religious upbringing.

“When I was 12, my father applied to be rabbi of the local shul,” Hammer-Bleich said. “After he did not get the position I was tremendously relieved. How would I have been able to express my anti-religious ideas with him as rabbi? How would I have been able to not go to Shul?”

Kalendar also acknowledged this level of expectation that comes with being the child of a rabbi, but explained that he did not blame anyone for thinking he should behave a certain way because of his upbringing.

This pressure surfaced both at synagogue and at school. Kalendar said that he felt an expectation to be a “perfect goodie goodie Jewish boy” and know the answers in his classes because of his father’s position.

Senior Manny Bass, whose mother is a rabbi and father is a cantor, echoed Kalendar’s feelings of pressure, but added that he felt more like a messenger than anything else.

“Both at shul and at school I feel like I am the way that a person could communicate to my parents,” Bass said. “In the B’nai Mitzvah circuit, every one of my friends would ask me to ask my dad to go easy on them, and countless people have asked me to tell my mother to give them good grades,” Bass said.

Jewish Text teacher Janet Ozur Bass, who is also Bass’ mother, alluded to the challenge of always being “in [her] kid’s space” as well.

“I think the hardest part for our kids is that they can’t escape from us,” Ozur Bass said. “I’m here in the school and my husband is there at shul. If there is a guest speaker at their youth group, it is going to be their dad. So I think that’s the flip side of it and I think different kids who are clergy kids will react very differently to that.”

All in all though, Ozur Bass feels that she has a responsibility to contribute to her children’s Jewish education on a more personal level, regardless of their decisions to follow in her footsteps or not.

“I think what we do here at school is much more teaching about Judaism, not teaching about how to live Judaism,” Ozur Bass said. “At home, we teach them this is how you live.”