In 1986, my mother worked as a receptionist in a medical suite attached to a hospital in Tehran, Iran. After two years of employment, her coworkers informed her boss that she was Jewish. Rather than showing support for his employee, he called her into his office to discuss potential dismissal from her position.

After much back-and-forth deliberation with her boss, my mother decided that her workplace was no longer a welcome space for her, and quit. This turned out to be just one of the many occasions that my mother and her family felt discomfort in their homeland.

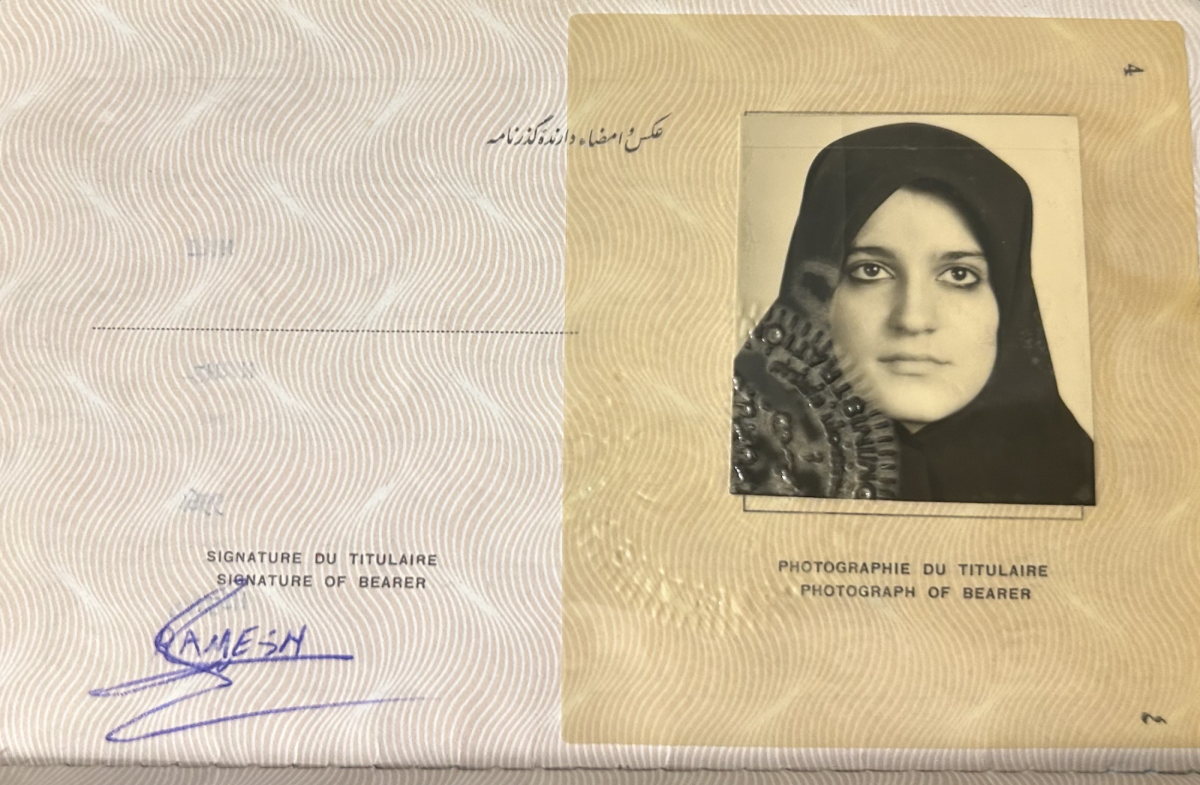

There is only so much discrimination a person can handle, so in 1989, my mother finally got her visa out of Iran. She felt a weight lift off her shoulders, even though leaving Iran meant she had to live in Italy alone for two years until she could immigrate to the United States where she would eventually build a new life for herself.

My mother’s immediate family was less fortunate though, as they were only able to flee Iran almost 11 years later when they moved to Israel. This is where they were able to live much richer lives, full of religious freedom and liberty, circumstances which they were not fortunate enough to live through in Iran.

Hearing the perspectives of my loved ones who managed to escape such an oppressive government was eye-opening. The more I heard of the discrimination they faced under the Islamic regime, the more I loathed it. The hateful feelings that I had built towards the Iranian government only strengthened over the years as I learned of other minorities being discriminated against in my parents’ birthplace.

In 2022, I began to understand the oppressive Iranian lifestyle beyond my parents’ experiences. One particularly moving tale was the story of Mahasa Amini, an Iranian woman who died in the custody of the “morality police” after dressing “inappropriately” by not complying with the Iranian dress code that required all women to wear hijabs in public spaces. This incident led Persians and Iranians worldwide to speak out against the terror ensuing in Iran, with protests and riots occurring globally in support of Amini.

While this was an intense case of unjust treatment toward women in Iran, it wasn’t the only one. After Amini’s death was publicized, I learned that my mother faced a similar situation many years ago when she was nearly arrested by the “morality police” for showing too much of her hair. Luckily, she was able to get herself out of that intimidating situation. Although, this is not the case for most women in this position.

Regardless, once I heard this story, it came to my attention that even though the people in Iran weren’t my neighbors, I was still connected to them because of my background and the fact that my family was once in their shoes. I felt the need to support the women and civilians living in Iran because I could not support my own mother through her difficulties there.

So on April 13, 2024, a particular sense of disgust struck me as I read online that Iran sent 300 missiles and drones toward Israel, the country that brought my mother’s family a sense of security and welcome during their trying times in Iran. While tensions have been high in the Middle East since the attack on Oct. 7, this strike was particularly sensitive to me. I felt isolated from my ethnic community as a divide had just been imposed.

Before the attack, I was proud to express all aspects of my identity: as an American, as a Jew and as a Persian. But when Iran sent the missiles, I knew that I had to stand by Israel, the nation I always knew to be in the right, even if it meant losing the connections with the Persian society I once valued dearly.

While I felt true pride in seeing a plethora of Jewish figures standing up for Israel online, I felt a sense of grief as I blocked my favorite Persian-American content creators who posted in favor of the terror that Iran took part in. Not only did I feel a disconnect from the online community that I once stood amongst, but I felt ashamed that I was ever associated with them.

Something that continues to provide me with some sense of relief though, is seeing the group of Iranians who do stand alongside Israel. While there are a handful of Persian Jews like me who are in support of the Jewish state, there is something especially comforting about the non-Jewish Iranians speaking out against their own kind in support of what they know is right, even if they know that there would be consequences.

One prominent example of this is the case of the famous Iranian volleyball player, Mobina Rostami, who shared her position on social media on the night of Iran’s strike on Israel and was later arrested.

“As an Iranian, I am truly ashamed of the authorities’ attack on Israel,” Rostami posted on Instagram. “But you need to know that the people in Iran love Israel and hate the Islamic Republic.”

Reading this post, I felt some of the faith I had in the people of my ethnicity restored. I don’t need to burn all of the bridges that connect me to my background as a Persian because the people of Iran are not the Islamic regime of Iran.

Coming to this understanding helped me accept that no matter what, my parents came from Iran and I am Persian. Although this situation has brought me much closer to my Jewish roots, I still appreciate the connection I have built with my ancestry and can continue to do so while upholding my personal values.