At any other time and place, it would be highly surprising to see a gaggle of reporters from around the world, standing in front of a Veterans of Foreign Wars clubhouse in 10 degree weather, interviewing me, a teenager. However, during the New Hampshire presidential primary this was par for the course.

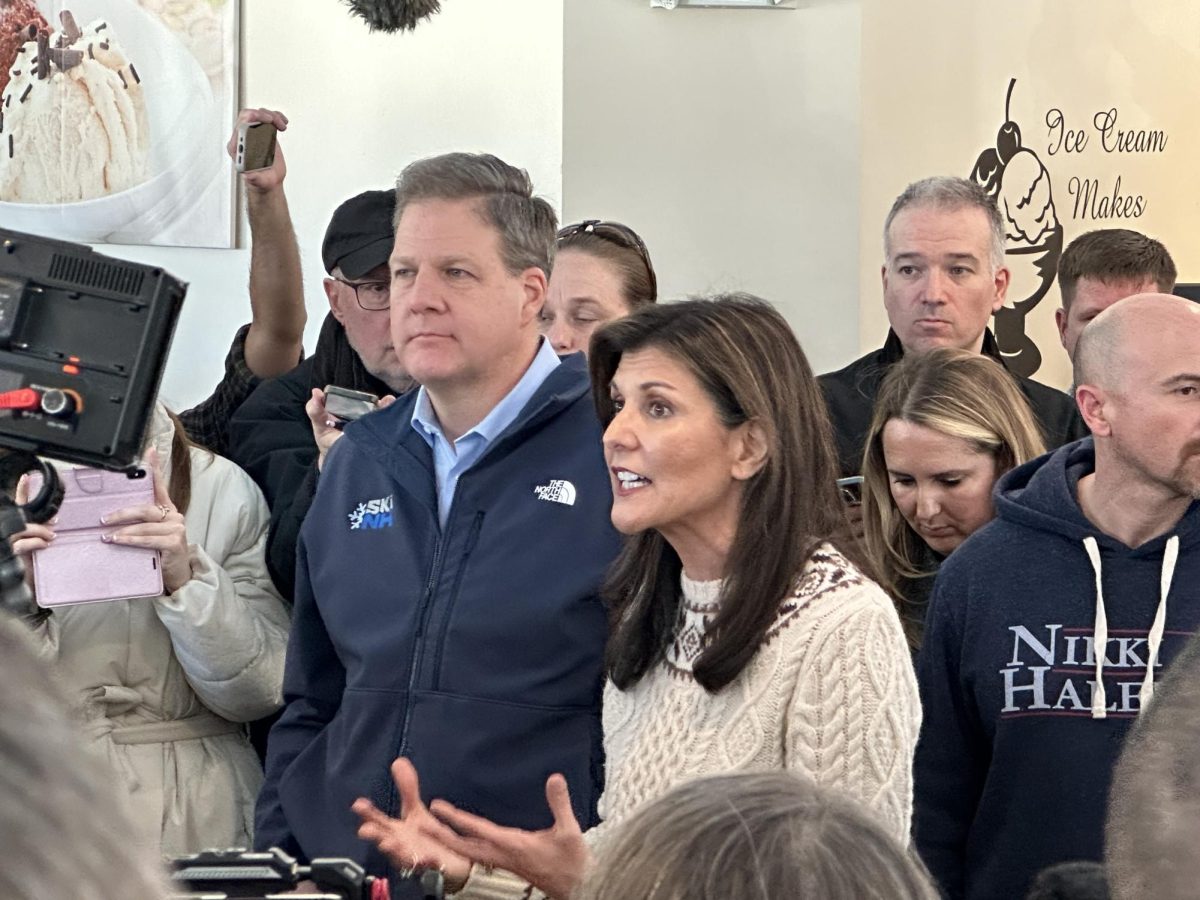

The New Hampshire presidential primary, which was held on Jan. 23 this year, has long been the first presidential primary in the nation, which means that presidential hopefuls have typically invested an extraordinary amount of time and money attempting to win there. As New Hampshire Governor Chris Sununu recently explained, presidential candidates have traditionally attempted to win New Hampshire residents’ votes by campaigning “Person to person. Town to town. Small business to small business.”

During my time in New Hampshire over the course of the three action packed days leading up to primary day, I attended seven Nikki Haley events from Nashua to Exeter; waited in line for two Trump events in Manchester and Rochester (but got into neither due to room capacity); and attended one Dean Phillips event in Rochester. Across my three days, I had the opportunity to watch history in the making and the political process up close and personal. In those three days, I got to learn about and experience both the anger and compassion that surrounds American politics.

On the Republican side, Haley’s campaign functioned like a typical New Hampshire presidential campaign you would see in most contested primaries. I saw her speak at a middle school, a high school, a college, a hotel conference room, two restaurants and the VFW hall. She gave variations on a stump speech that addressed domestic and foreign policy issues and included stories about being a military spouse and a mom to two kids. After her events, she would either wait as people came one by one to her or she would walk around to people who would ask her questions and take pictures with her. Hers was an old-fashioned campaign very much focused on persuading voters to support her.

Trump’s campaign, on the other hand, functioned much like what one would expect from an incumbent president. He gave relatively few speeches, always to large crowds at big venues such as opera houses and arenas. Those who signed up for Trump events received texts from his campaign that suggested arriving up to five hours early. When I asked one of the security guards how early one needed to arrive in order to ensure getting in, he replied by saying that people had been waiting at the arena doors since 8 a.m. (even though the event was scheduled to start at 7 p.m.).

For the second Trump event I attempted to attend, a rally at the Rochester Opera House, I arrived about three hours early. I waited in a line outside that spanned six city blocks in 15 degree weather. There were numerous vendors selling Trump paraphernalia much like there are vendors outside of Capital One Arena or Nationals Park. While I was waiting in line, two trucks from the Lincoln Project, an anti-Trump political action committee, kept driving up and down the street with giant screens playing an ad called “God Made a Dictator.” One man near me chucked snowballs at one of the trucks and hit the truck driver right in the face, all while the chucker yelled obscenities at the truck driver in a heavy New England accent. From this, I was able to get an insight into the dark side of politics; the anger and rage that people have for the other political side.

On the Democratic side, Phillips ran a campaign that felt similar in tone and scale to Haley’s. At the one Phillips event I attended, he stood in a packed room in Rochester giving his stump speech and then answering the audience’s questions. At one point, an older man stood up. He said that when he was younger he felt all alone, and afraid, in Rochester as a gay man. Then he tearfully thanked Phillips for his support of the gay community. Phillips walked over to the older man and gave him a hug, demonstrating the sort of empathy that maybe might have been at home at a Haley event but definitely not in a Trump event.

Each presidential campaign event in New Hampshire was attended by reporters from around the world. I was repeatedly approached for interviews. Most American reporters seemed to prioritize New Hampshire residents’ perspectives. So, other than a New York Times reporter, the American correspondents rarely proceeded with interviewing me after they learned I was from Maryland. In contrast, international reporters didn’t seem to care. I was interviewed by reporters from France, Sweden, Germany, Japan, and Korea. Many of these reporters were their outlets’ Washington correspondents, who had come to New Hampshire just for the primary. What I found interesting was that the same correspondents who cover the whole United States from a lot of the major international newspapers were in some random town in New Hampshire, anxiously waiting to interview random New Hampshirites.

Residents of New Hampshire, with its first-in-the-nation primary election, see far more presidential hopefuls than do residents of any other state except Iowa (the first-in-the-nation primary caucus). Joining them for a whirlwind weekend enabled me to participate in, and learn from, American political history as it happened.