Under pressure

Grappling with political correctness

March 11, 2016

“Stop calling me racist,” junior Jared Bauman typed in the first line of his most recent post published on Jan. 2. “I am not kidding. Please, stop calling me racist.”

Bauman runs a political blog called “The Young Participant,” and in his latest entry he addressed a topic whose prevalence has increased recently on college campuses, social media and in the CESJDS classroom: political correctness.

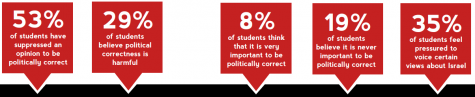

According to a recent survey of 249 Upper School students, 53 percent have suppressed a thought or opinion in class in order to be politically correct. Bauman believes that for this reason, political correctness negatively affects discussions and limits people’s ability to honestly express themselves.

In addition to impeding conversation, Bauman argues that political correctness can lead to destructive name-calling of those who think outside of popular opinion.

“There are so many times just in the world where someone tries to raise a concern they have about a certain issue, and are immediately called racist or intolerant or xenophobic or Islamophobic or homophobic … simply because they don’t think in a way that many other people do,” Bauman said.

Bauman experienced these insults firsthand at a Junior State of America convention, where he spoke against gender-neutral bathrooms because he believed they would harm transgender people rather than help combat bullying. Despite expressing what he thought was a rational argument, Bauman was dismissed and told he was “too privileged” to speak his mind on the subject.

“There’s way too many times in certain kinds of public forums where my opinion has been discounted or attacked, simply because my background is not one where I was oppressed, or I’m not a minority, according to general American thought,” Bauman said.

Alumnus Cole Aronson (‘14), a current sophomore at Yale University, often faces pressure to be politically correct on his college campus. While he believes that some of his classmates are perpetrators of this unnecessary pressure, many Yale students agree with Aronson that it can be difficult to freely express authentic opinions on campus. According to a recent article published by the Atlantic, 66 percent of Yale students who attended a debate on the topic agreed that free speech is threatened on campus.

For Aronson, adhering to political correctness means suppressing authentic thoughts to avoid offending certain people. Aronson believes these people are “almost invariably” marginalized members of society, and that it is easier for people who come from socially disadvantaged backgrounds to fully express their beliefs without criticism.

“The people listening to what somebody is saying, in my experience, will judge the same substance vastly differently if the person is not straight, is not male or is not white,” Aronson said.

According to Aronson, pressure to be politically correct serves as a “muffle” not only for the privileged, but for anyone who does not fit the stereotypical mold of their group.

“If you look at the way black conservatives are treated, it’s disgusting,” Aronson said. “If you look at the way that pro-life women are treated, it’s disgusting. So one of the things that the modern left has tried to do is [typecast] demographics.”

While some students at Yale have gone so far as to refuse to listen to Aronson’s ideas, he remembers that most of his classes at JDS provided more accepting atmospheres for discussion.

Aronson specifically remembers this being true for his Arab-Israeli Conflict class, which was taught by the current Academic Dean Aileen Goldstein. He remembers that Goldstein “gave credence to all opinions,” which helped in preventing any student from being ostracized for his or her beliefs.

This inclusiveness reflects the type of environment that the JDS administration aims to cultivate in all classes. According to Goldstein, while JDS does not administer any specific training on political correctness, the school does try to generate a healthy atmosphere where students can practice critical thinking and develop individual ideas. The faculty is taught how to deal with topics such as gender, sexuality and diversity. This training has come in part through workshops, where, for example, JDS has collaborated with Operation Understanding D.C. to learn how to speak about race.

For Goldstein, another major aspect of creating healthy and respectful classroom environments is exposing students to multiple perspectives on political and social issues. Goldstein believes it is the responsibility of teachers to provide these different viewpoints while keeping their own opinions out of the discussion.

“It’s not about the faculty’s perspective, it’s about the students and cultivating their thinking,” Goldstein said. “It is not our job to be sharing those opinions, it is our job in classes to be cultivating the conversation.”

For Jewish History teacher Aaron Bregman, the current teacher of the Arab-Israeli Conflict class, one important part of sustaining an open atmosphere for discussion is providing his students with a variety of perspectives on the conflict. Although Bregman is openly a Zionist, he remains impartial in the classroom for the sake of his students.

“As a history teacher I feel … that I need to provide the whole narrative,” Bregman said. “I need to push students on the devil’s advocate viewpoint because if I don’t, then I’m not doing my job the way it should be done.”

Freshman Beyla Bass also believes that having an open mind when approaching the sensitive topic of Israel can result in more compatible learning atmospheres. Therefore, she finds it troubling when people fail to acknowledge perspectives other than their own.

“They want to voice their opinion from their Jewish side without taking into account the side of the Palestinians, but to be politically correct and to have an informed opinion you have to know the sides of the different people,” Bass said.

According to Bass, political correctness can be used in a more positive way to foster respectful discussion. She believes it not only acts as a filter that forces students “to put more thought” into their speech, but also validates their opinions by making them “sound more informed.”

Like Bass, junior Joey Rushfield believes that political correctness is an important filter for discussion. For Rushfield, political correctness helps facilitate the respect all people should practice.

“Things like using slurs? That’s hateful, not just politically incorrect. Invalidating someone’s sexual or gender identity? That’s oppressive, not [just] politically incorrect,” Rushfield said. “People often forget that political correctness is meant to help those who are marginalized and avoid adding to society’s discriminatory attitudes towards them.”

Rushfield actively intervenes when he sees this lack of respect. While volunteering as a counselor at the eighth-grade shabbaton, Rushfield overheard students using anti-gay slurs and made a point to correct their language. He believes that this intervention is always necessary because a person’s right to “be edgy” should never impede on someone else’s right to happiness.

While Rushfield sees political correctness as an absolute necessity, Bauman struggles to weigh its benefits and consequences. He believes that it is necessary to find a balance between dealing with a lack of sensitivity in speech and having completely restricted speech.

“Political correctness can be something good if it’s used in healthy amounts, but it’s our duty as people to not use it as a political weapon,” Bauman said.

results from a survey of 249 out of 523 Upper School students